Mindfulness has been incorporated into businesses since the 1970’s, and over the past several years it has become a buzzword in office environments of companies such as Google, Apple, and Nike. Mindfulness is becoming a central part of culture and management.

While mindfulness is talked about as a contributor to reduced stress and increased productivity, I have seen relatively few effective explanations about *how* it helps.

Recently, at BayWa r.e., we started doing a mindfulness meditation at the beginning of each day’s leadership team huddle, and I thought I would share our experience to try to provide some insight into that question.

Why practice mindfulness?

The idea behind mindfulness practice is that by continually reporting on one’s internal state of being—and on one’s interaction with the environment—one can achieve a higher level of awareness.

One way to think about mindfulness practice is that you are cultivating a voice in your head that continually reports back on what is happening. “I am hearing a bird chirping in my neighbor’s tree.” For example, “I am feeling warm, and in my lower back I have some soreness.” “I am feeling sad.” Etc. The more you do this internal reporting, the more the voice becomes automatic.

Sensory input, emotional feelings, physical feelings, all simply get named; there’s no attempt to explain, suppress, or otherwise engage with them. Common teachings suggest that spending a few minutes a day practicing this self-reporting can be beneficial. But in my experience, expanding the mindfulness practice to as much of one’s waking life as possible significantly multiplies the impact.

How is it useful?

We tend to think we are conscious of all the choices and actions we make, but this is far from the case. In fact, research continues to show we are conscious of only a fraction of the decisions that underlie our actions.

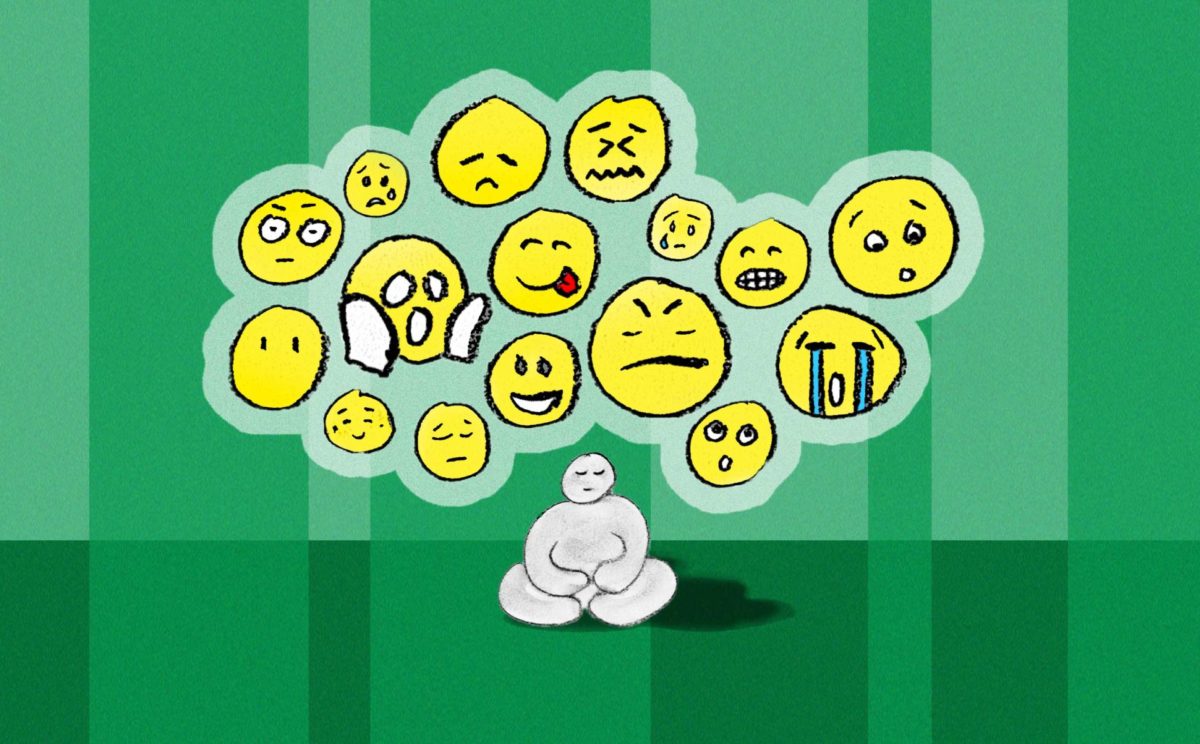

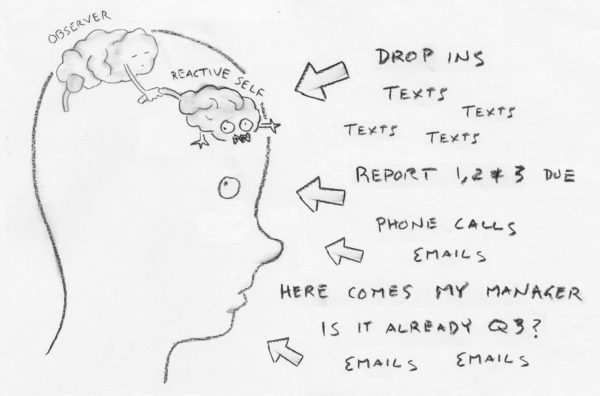

In the workplace, we are continually bombarded with emotionally-loaded content from external and internal sources: unhappy colleagues, frightening news, frustrating policies, unethical competitors, and yes, our pre-wired beliefs about ourselves. Each interaction with these stimuli causes a certain degree of emotional reaction.

For example, when one of my co-workers questions a decision we have already made and acted on, my initial reaction might be to get frustrated. Let’s call this frustrated part of my mind the reactive self. This is the part of all of us that makes choices unconsciously.

The practice of mindfulness (continually reporting on my internal state) can strengthen what I call the observer. This observer is an internal voice, one level “above” the reactive self, which helps me notice my reactive self getting frustrated. In short, there is an “I” that experiences an external stimulus, and a “higher I” that observes me having that experience.

By noticing my frustration, my observer allows me to intervene before my emotional response is acted out. The stronger my internal observer gets, the more it helps me acknowledge my frustration (not suppress it) and evaluate my co-worker’s input from a more calm, rational perspective.

And while much of our experience involves living out a recursive loop—cycling between stimuli and reactive self—if we learn to empower the observer, we can interrupt that loop, and the result is a more thoughtful, intentional and, some say, ultimately more meaningful existence.

Our approach to the mindfulness practice

1) Five-minute mindfulness meditation

During these five minutes, the intention is to experience the internal and external circumstances of that very moment. It includes guidance like: “Notice the feeling of your feet against the floor, and the pressure of your shoes on your feet.” Or, “Roll your shoulders and feel any crackling, pain, or tension, that is released as you do so.”

(Note: We began with David Dunlap, our VP of Operations, guiding the meditation. since he had some experience. But in the past few weeks other members of our executive team have started taking turns leading, with the goal of being able to bring this into other parts of the organization. It’s not as difficult as it seems at first!)

2) “3-fold breath”

The leadership team does this as a group and is a practice I picked up from a Wilderness Therapy program (shout out to Open Sky). It goes like this:

- Breath #1 – deep inhale, then release the breath quickly, all at once, ending by compressing the abdomen towards the spine.

- Breath #2 – same as #1.

- Breath #3 – deep inhale, and hold the breath until it just starts to get uncomfortable, then exhale slowly—bit by bit—until the chest and belly are fully compressed. Then release control of your breathing and allow it to return to normal.

3) 4-line check-in

Each leadership team member reports on:

- How are they feeling in their body?

- In their heart?

- In their mind?

- In their spirit? (This has no religious underpinning, and no particular definition of “spirit.” Spirit may be substituted with “higher mind”— where morality and values live, for example—as opposed to rational/intellectual material that lives in the “mind.” Or you could just skip this one if it makes you uncomfortable.)

The results

The results I notice in our daily leadership huddles include:

- More “intentional conversation”, with less interrupting, fewer tangents, and steadier pace

- Less “rescuing” one another (when we’re aware someone in a meeting is feeling bad, we tend to want to distract them, or we might passively try to shield them from questions or tasks. This happens less.)

- Clearer requests for clarification, decisions and action items

- Increased empathy for teammates, and stronger connections between them

- Clearer in-the-moment feedback and straight talk, with less likelihood of defensive or other emotional reactions surfacing in response

I attribute these effects to the heightened ability of each leadership team member to observe their feelings and reactions more fully in the moment, and have greater capacity for conscious choice in the moment about their statements and reactions – in my opinion, supported by having a consistent mindfulness practice.

If you are interested in trying this out, my advice is that you try doing a four-line check-in in your head between tasks throughout the day. See if you notice your experience changing, and whether you are a little calmer and more intentional about your actions as a result.

Anything we can do to nurture the observer in ourselves as leaders, and in our teams, can result in steadier and more rational working relationships and decision-making, and can therefore contribute directly to the efficiency and effectiveness of a business, and to its ability to execute its strategy and realize its vision.

Good stuff Boaz. Not sure mine is as structured but introspection is something I spend time on each day.