Constrained PM – Illustration, Tom Miller

Constrained PM – Illustration, Tom Miller

How many times has this happened to you? You decide you need to update your strategic plan. You get your team together. You do a SWOT analysis. You do a value stream map. You do a customer journey map. You define “what winning looks like.” You distill strategic objectives and design a multi-year roadmap to achieve them. And then you wait. And wait. And nothing happens.

You wonder if your team is engaged. You wonder if the market is too volatile. You feel understaffed. You wonder if your whole organization will always be too busy putting out fires to work on strategic objectives. And you— and your team—slowly lose hope that you can control your destiny and work on what you know, deep down, may not be urgent but is critically important.

For the past three years, BayWa r.e. Solar Systems has undertaken a variety of strategic planning methods in an effort to break free of these patterns. Recently, we launched a revision that I feel—(knock on wood)— is not just a new iteration, but is actually a culmination of lessons learned in strategic planning. So I thought I would share it with you.

First, let’s cover some basic tenets:

- Strategic execution (executing a strategic plan, as opposed to daily work) is a cross-functional exercise. Even in a small organization, dividing strategic objectives among team members can lead to confusion about whether they are running one project or multiple ones. Furthermore, there are interdependencies, sometimes subtle, in the work different team members, or teams, are responsible for. That means that everyone having their own independent strategic priority is probably unrealistic.

- Every organization has a constraint. In a manufacturing line, it’s where inventory piles up. In a service business, it’s where information tends to get stuck where promises aren’t kept as consistently, where interdepartmental friction tends to fester, etc. There is no shame in being the constraint—every organization has one. But there is risk in neglecting to account for the constraint in business planning.

- Eliyahu Goldratt’s Theory of Constraints provides a productive way to apply constraint-thinking: Only one constraint matters at any given time. To “deal with” it, you take the following four steps, in this order:

- “Identify” it

- “Exploit” it (increase its utilization rate as much as possible)

- “Subordinate” other resources to it (stop trying to achieve more throughput than your constraint can handle) and

- “Elevate” it (invest in more capacity at the constraint)

So. Let’s take, for example, a scenario in which a contracting company’s strategic goal is to become the most trusted expert in meeting customer expectations throughout the installation process. This fits with the company’s core capabilities, which include solid project management and some innovative shop-work, reducing time on the job site, and absorbing schedule risk by getting work done outside the job schedule.

This strategy will enable differentiation, reduce dependence on selling specific brands in a volatile market, and increase trust with customers, resulting in better referrals, better close rates, and better margins.

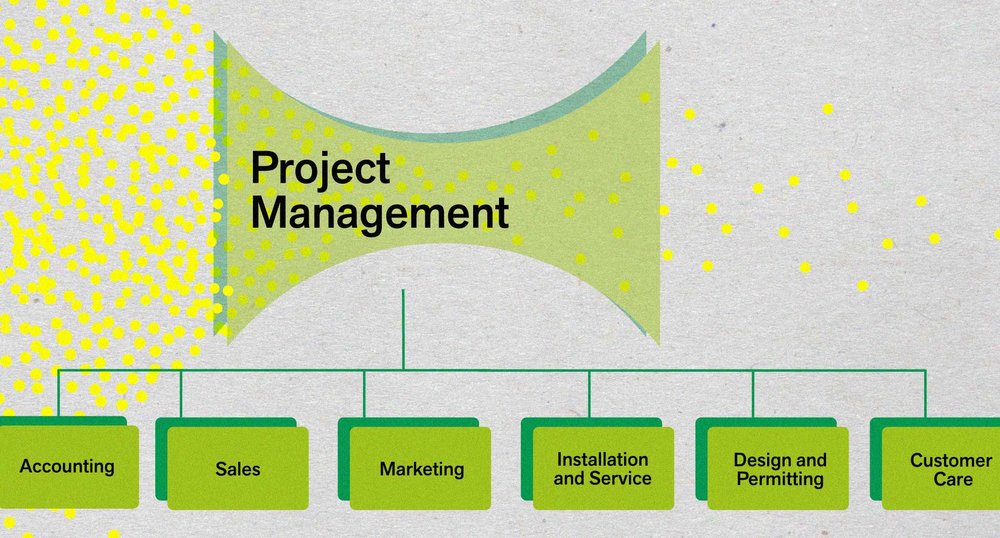

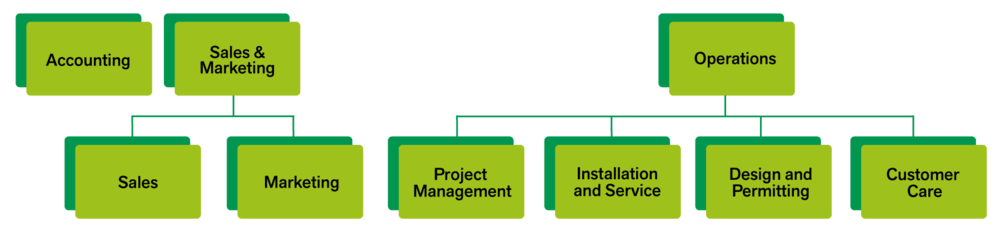

The functional teams in the company are:

In the above team example, let’s pretend the constraint in the organization is Project Management. This is evident because it is difficult for PM’s to keep the CRM up-to-date, materials purchasing is often last-minute, and schedule changes occur frequently.

Obviously, a constrained project management team means customer care, installation, and other parts of the organization sometimes lack the information they need to make good decisions, and customer experience suffers.

A typical next step could be for the leadership team to assign strategic priorities to each functional team, for example:

- The Customer Care Team will call every customer weekly with updates (with about forty active customers in some stage of project management, this means eight calls per day)

- The Marketing Team will develop sales materials featuring the transparent construction process, a la: “our pledge is to call you weekly, finish the job on time, etc.”

- The Sales Team will implement trainings to sell transparency instead of product features

- The Installation Team will report twice per day on project progress instead of only at end-of-day

- The Project Management Team will use the CRM daily to update projects

- The Finance Team will include project progress information with billings

Etc.

Sounds like great cross-functional alignment is taking place, right? Well, let’s see what happens:

Customer Care calls every customer weekly. Marketing develops new sales materials. Sales changes its pitch. Finance includes a letter with each billing.

But Project Management fails to update the CRM.

Because of this, Customer Care doesn’t have current information, so the new weekly calls annoy customers. Sales is frustrated because it is making promises the company can’t keep. Finance pesters Project Managers for information. You get the idea.

So what went wrong?

I’ll tell you: nothing changed to make the Project Managers’ strategic priority (keeping the CRM up to date) more feasible. Management decreeing that “it will happen” does not solve the problem.

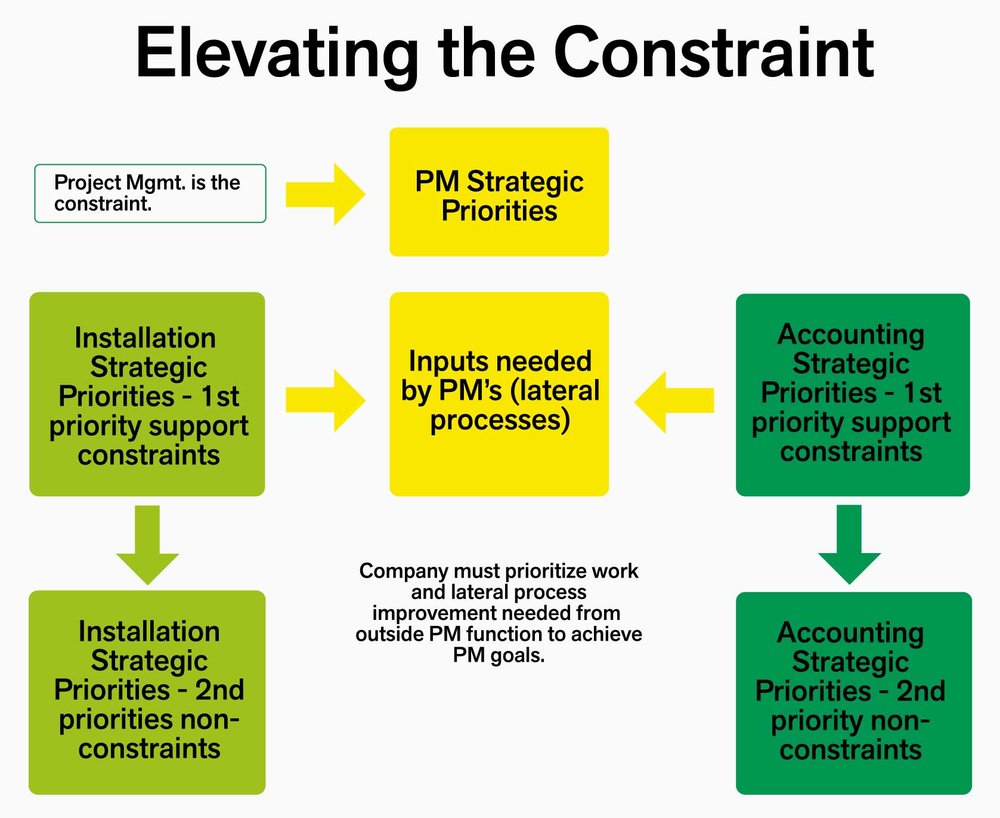

To really solve the problem, the Project Management Team’s strategic priority needs to be “elevated” by all the other relevant departments. In other words, the inputs required by Project Managers to update the CRM need to reach them in a more useful way, so the CRM has a better chance of being updated consistently.

Instead of each team “silo” working independently to advance the company strategy, team leaders need to instead look at the cross-team processes that can be created or improved to increase Project Management success.

Now let’s look at some options to disrupt this negative pattern:

- Instead of calling eight customers each day, call all forty on Monday. To achieve this, have all installation crews knock off early the Friday before, come into the office, and work with PM’s and the design/permitting team to get all job information updated and a new schedule set for the following week. What does this achieve?

- It subordinates other functions to the constraint. Yes, someone overseeing the organization might freak out if fewer jobs are installed on Fridays. But the reality is that, while those jobs are being installed, the disruptions in equipment supply, schedule changes, and less-than-stellar customer experience are costing the company in the long run. But with a clean project schedule, and new customer expectations reset each Monday, jobs will now run more smoothly and customers will be happy.

- It elevates the constraint. When the design and installation teams gather to report on jobs, they are also helping the PM team get its work done, effectively increasing capacity.

- Instead of having the finance department send billings immediately on milestone achievement, invoices could be sent once a week— again, after weekly time is dedicated to PM’s updating the CRM. This would prevent accountants from having to badger PM’s for milestone and scheduling information. The same benefits described in the previous example apply.

- For simple projects, installation crews can report into Customer Care directly, who updates the CRM. Only complex projects get updated by the Project Managers. This is “exploiting” the constraint – making sure that the constraint only does the work that it alone can accomplish.

Making sense?

The key is for the other departments to readjust their workflow in ways that either give the PMs the right inputs, at the right time, more effectively OR avoid the need for PM’s involvement altogether.

So, the obvious question a manager would ask is, “if my Customer Care Team calls every customer on Mondays, what does it do the rest of the week?” The terrifying answer is: whatever they want, as long as it doesn’t create more work for the project management team. This is what is meant by “subordinating” in TOC.

Note on the above: When extra capacity exists—anywhere in an organization—the temptation is to utilize it. This is certainly not a bad idea, as long as using the excess capacity in no way creates more work (or complexity of work) for the constraint.

Some additional food for thought: as most companies grow, the entrepreneur/ founder often finds itself to be the constraint, as opposed to a team in the organization. No amount of improving lateral process prioritization can solve this – it is purely a question of pushing empowerment and accountability to the employees. The only other option is to accept that the throughput of the company will never be greater than the throughput of the boss’ slowest process.

Finally, one might read this article and think, “why don’t they just hire another Project Manager?” This may be a good decision. However, before increasing capacity, changing the workflow in a way that better utilizes current capacity is more effective. While it is very likely that hiring another PM might increase capacity in the short-term, failing to exploit existing capacity—and subordinating other departments to it— postpones dealing with the problem, prevents growth in throughput, and detracts from the company’s ability to provide the most transparent workflow for its customers.

So, bringing it all together: what can you do differently to increase success?

- Identify your constraint, and talk about it openly in your organization

- Identify your constraint’s strategic objectives first

- Ask the people on the constrained team what they need from other departments to achieve their strategic objectives

- Insist that other teams prioritize the constraint’s strategic objectives over all others

- Only spend time on other strategic projects after the ones that serve the constraint are complete.

Good luck in your strategic planning, and let us know if you need help!